For several thousand years, Vietnamese Traditional Medicine has evolved under the shadows of Chinese Traditional Medicine, culture, and rule. At this point in time, it is nearly impossible to separate out and delineate Traditional Vietnamese Medicine (TVM) from Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) because their developments were so inter-twined. This is a brief history of the development of TVM and its influences particularly by Southern China.

What is generally considered classical Vietnamese culture started in the northern third of Vietnam. This area was very much connected to China and Chinese culture even before the 4th or 5th century B.C. During that time period, southern China, from the Yangtze River to the northern part of VN, was one large ecological region. There were a number of different ethnic groups living in this fertile region who were not considered Chinese by Northern Chinese. Among these groups was the ‘Yue,’ the Chinese word for Viet. Northern Vietnam and Southern China came under Chinese rule by the 4th century B.C.

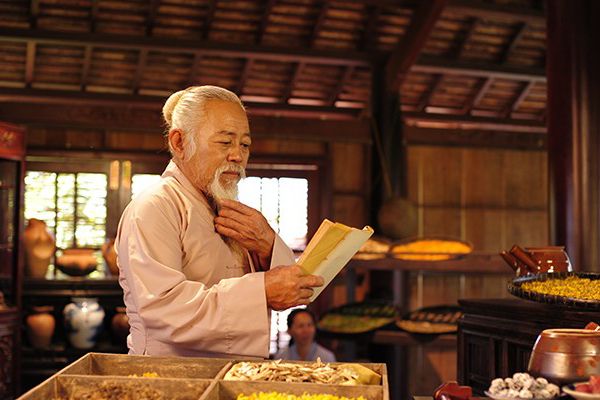

Medical texts and instruments found in Northern Vietnam have been shown to predate Chinese conquest, suggesting that Vietnamese people already had a developed system of medicine. In addition, among Chinese medical texts from the 4th century B.C., references were given to the “Yue Prescriptions,” indicating that “Traditional Vietnamese Medicine” was already written. Traditional Vietnamese and Chinese Medicine continued to evolve closely for the next millennium. As part of the conquest, the Chinese abstracted medicinal drugs, among other valuables, as tax and tribute. In so doing, folk medicine from Northern Vietnam was incorporated into Traditional Chinese Medicine. Likewise, Traditional Chinese Medicine and culture were introduced to Vietnam during the one thousand years Chinese occupation. Their interrelationship can be observed by the influence of TCM theories on the TVM, and the empirical applications of local Vietnamese medicinal in TCM. In practice, TCM practitioners would spend more time giving their patients a sort of theoretical explanation of what’s going on, whereas TVM practitioners would use a more practical approach and concentrate less on theory. In the 17th century, traditional Vietnamese, Chinese and practitioners from other ethnic groups began identifying their medicine as Eastern medicine or Dong Y (This is also referred to as Oriental Medicine) to distinguish their traditional medicine from the Western colonial medicine. In this article, Dong Y is used to refer to both Chinese and Vietnamese traditional medicine.

Traditional Dong Y (Eastern Medicine) Theories:

As described above, Traditional Chinese and Traditional Vietnamese Medicine differ in practice, yet they share the same theoretical foundation. The cornerstone of Dong Y theories is based on the observed effects of Qi (energy). Although there are as many different forms of Qi as there are different kinds of functions (Source or Essence Qi, Food Qi, Qi of the Mind or Shen, etc.), they are all related to the original Source or Essence and Food Qi. The Essence is inherited from our parents, while Food Qi is extracted from food. Furthermore, we see that Qi encompasses more than just Energy. It is also blood and “fuel” gathered and stored by the body. So, Qi is also the substance we call matter. As in Einstein’s theory of energy and matter, that E=MC2, or that matter is essentially energy. Blood and Qi are like matter and energy; they are different states of the same element.

The functions of Qi can be summarized as: 1) providing movement, 2) defending the body from pathological factors, and 3) supporting/promoting growth and development. The functions of Blood can be summarized as nourishment and moistening. Blood nourishes Qi and Qi moves Blood. As in physics, the concept of Qi is also universal – our energy and that of the universe is transferable. One can deplete one’s Qi by strenuous work, poor diet and lifestyle. Conversely, one can also harvest energy from the universe by maintaining optimal health and by practicing some forms of breathing exercise like Qi Gong.

Dong Y’s major theories are: Yin and Yang, Five Elements, 12 Organs, and 14 regular meridians. These theories are often combined to explain a health condition. The following are brief summaries of these theories.

Yin and Yang is probably the oldest and the most significant theory in Dong Y. It describes the existence of and the importance for balance between opposite states (cold and hot, inaction and action). Yin and Yang can be divided into three divisions: 1) Cold versus Hot; 2) Interior versus Exterior; 3)Deficiency versus Excess. Yin conditions are typically manifested by symptoms of cold, interior, and deficient while Yang conditions are typically manifested by symptoms of heat, exterior, and excess. Invariably, chronic deficiencies in one organ/element typically lead to an excess or deficiency in another organ/element. It is believed that some organs naturally possess more Yin while other organs more Yang, but all organs have a Yin and a Yang counterpart. For example, the stomach’s processing of food is considered a Yang function. However, this function depends on enzymes and acid secretions (Yin substances). Consequently, when one’s Yin within an organ is weak, one’s organ function is affected. In the case of stomach Yin deficiency, one will see a Yin type of mal-digestion, whereas Stomach Yang deficiency will lead to a Yang type of mal-digestion. Each syndrome requires a specific form of treatment. A Yang or Qi deficiency of the Stomach can be exacerbated by supplementing Yin tonics and vice versa. See Yin and Yang for additional comparisons.

In the Five Elements theory, health is viewed as balance between five major entities (Fire, Earth, Metal, Water, and Wood). Observing these elements in nature, Dong Y medical theorists keenly relate these same concepts to our health. Furthermore, the organs are also organized into the traditional Chinese court system (Emperor, Prime Minister, Treasurer, etc). Thus, organs with complementary functions, or have similar symbolic relationships are paireed. In light of all of these relationships, the heart and small intestine are considered “Fire”. The stomach and pancreas are designated the “Earth”. The lungs and large intestine are “Metal”. The kidneys and urinary bladder are “Water”. The Liver and the Gall Bladder represent “Wood”. Click to view Five Element’s chart. These elements together can create a constructive or destructive relationship. For example, Water is nurturing to Wood (constructive) yet it can put out fire (destructive). Furthermore, each element has a creative (nurturing), draining, destructive, and controlling relationship with another element. This simple model is expanded to encompass human physical, mental and spiritual health. Thus, a person with one weak element can lead to an excess of another element. For instance, a deficiency in water often leads deficient wood and excessive fire elements. A person of this profile is often thin physically, and with yin pattern conditions. Some Traditional Chinese Medicine schools base their entire approach on teaching the Five Elements theory.

The 12 organs and the corresponding 14 regular meridians are paired with each other based on their energetic functions that are beyond the scope of this paper. Both organs and meridians are organized into Yin and Yang partners. The functions of the Yin organs and meridians are generally associated with structures, quiescence, extracting pure substances and nourishing. The Yin meridians are in the front and on the inner side of the limbs. In contrast, Yang organs and meridians are generally associated dynamic functions, movement of Qi, and processing wastes. All organs and elements have a physical, emotional and spiritual component to health. Thus disturbances in each element can affect any level of health. Dong Y practitioners go back and forth between Yin and Yang, the Five Elements, the organs and meridian theories to explain illnesses.

In summary, the practice of Dong Y is guided by its theories, which are based on the concept of Qi. Blood and Energy makes up the Qi. This intimate relationship between Qi and Blood is essential for the daily bodily function, growth, learning and spiritual development. Thus, one’s health can be summarized by the functions and harmonies of one’s Qi and Blood, which can be quantified and if out of balance it can be corrected.

Diagnosis

Dong Y practitioners typically assess patient’s Qi and Blood by taking a medical history, observing the patient’s affects, and by feeling her pulses and examining the shape, size, and color of her tongue. By examining the pulses and tongue, a picture of disharmony between different elements within one’s body can be pieced together. For example, red spots on the tip of the tongue indicate that the person has/had a fever. Someone with poor digestion will tend to have a swollen tongue with multiple tooth marks. All disorders are described in terms of disharmonies between elements or between organs. For example, a patient with digestion problems may have diagnosis of Liver stagnation overacting on his Pancreas. Important comparisons in this area can be made between Eastern and Western approaches. In the East, diagnoses and treatments are more conceptual, ie, Wood overacting on Earth instead of stress or indigestion. However, behind this simplicity lie keen observations of ailment patterns (ie, emotional stress often affects digestion). Dong Y practitioners mostly focus their therapies on they syndromes, not individual complaints. Many users of Dong Y medicine would agree that the therapies are slow acting but the effects are long lasting.

Since Dong Y’s concepts encompass a broader function than biomedical models of organs, difficulties can arise when patients describe their complaints using Dong Y analogies to practitioners who are only trained in the biomedical approach. Other times, patients who are not aware of the differences between Western medicine and Dong Y, can also mistaken Dong Y diagnoses for Western pathologies. A common example is when a patient complains of a “weak kidney” insists that his kidneys be tested. When in reality this patient may have back or knee pain, urinary or sexual difficulties, coldness in the extremities, or early morning Another common complaint in the Vietnamese community is “hot liver.” In Dong Y, hot liver can refer to skin eruptions, itchiness, emotional irritation, or even hepatitis-some of which have no “direct” link to the organ liver.

Food Property (Chips and Melon):

A strong emphasis on dietetics is seen in Dong Y. In general, it is considered that people who are omnivorous are more prone to getting excessive “heat” accumulation. Many Dong Y therapies begin with changes to a patient’s diet, such as consumption of Congee or Chᯬ a porridge consisting of rice, a small amount of meat or tofu, and green onion or cilantro. People suffering from chronic illnesses usually eat this soup because it is easy to digest and very nourishing.

Vietnamese commonly refer to food property as hot or cold, which does not necessarily refer to temperature or spiciness. It refers to the effects that the food has on the body. For example, eating a plate of French fries can cause a person to feel very thirsty. Due to this effect on the body, fries are considered a hot food. Besides thirst, other symptoms of heat may include: skin eruption (acne), warmth or fever, constipation, irritability, insomnia, and a sense of “unwell”. Dried, deep fried or very rich foods (high sugar/fat content foods, even ice cream) are considered hot food.

On the other hand, melon and root vegetables are considered cool foods. Symptoms of cold or cool effects on the body may include: frequent urination and loose stool. Because the of the over-prevalence of “hot” conditions, people often refer to cool as a sense of “well being.” Fresh food, steamed or boiled vegetables are considered cool. Food preparation is just as important as the kind of food in determining whether it is hot or cool. For example, French fries are very hot compared to boiled potatoes. Food choices are often made based on their energetic qualities. Vietnamese regularly consumes squash in the summer for its cooling effects and more ginger in the winter for its warming effects.

The interpretation above also applies when Vietnamese people refer to medicine, particularly to the side effects of medicines. Medication with “hot” side effects like those that cause skin rash, itchiness, and thirst are considered hot, while medicines with the “cool” side effects such as loose stool would be considered cool. It is common to find that Vietnamese would take less medication than they were prescribed, drink herbs or eat certain food to “balance” a drug’s side effects. Unless this matter is approached with sensitivity, many would not tell their physicians about it; they believe that they are in the best position to judge their health needs or they just do not want to appear as disobeying authorities.

A number of Vietnamese consider French medicine more tolerable than American medicine. This cultural experience has shaped the behavior of many Vietnamese who frequently reduce their prescribed medication or seek similar medication or herbal treatments from acquaintances abroad.