The other day my 13-year-old granddaughter Van Chi came home very excited from school.

“Grandpa, is it true that you’re a relative of Mrs. Nhan, the grandmother of Hoa, my friend?” she asked breathlessly.

I was puzzled because Mrs. Nhan was a distant relative and we had not been in touch for some time.

“Why do you ask?”

“Because Hoa told me that your name, my name and the names of my mother, father and little sister are all mentioned in her family’s genealogical book.”

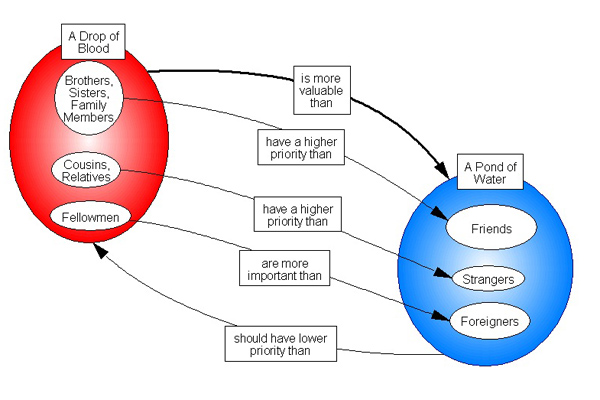

This little piece of information put me to shame and I felt guilty for having neglected the great family. Isn’t there a proverb that says “Giot mau dao hon ao nuoc la” (A drop of red blood is worth more than all the water of a pond)?

These days this adage, with its emphasis on consanguinity, may sound anachronistic. But until some forty years ago it was fairly common, especially in the countryside, to see three or four generations living together under the same roof. That was the type of homogenous family. In this economic unit members had a common denominator: as agricultural workers, often illiterate, they shared the same joys and pains and cultivated the same plot of land as well as the same set of ethical values based on Confucianism: the authority of old people, the superiority of men over women and of the father over the family.

Things have changed since 1945. Northern Vietnam in particular has undergone fast changes since the end of the war in 1975. The family is no longer what it used to be, structurally, morally as well as psychologically, as is reflected in many literary works, most typically in Nguyen Huy Thiep’s “General in Retirement” (1989).

For all the ideological and ethical controversy it has created, Thiep’s story remains to be a convincing sociological chronicle of changing times: a man who had risen from a liaison agent to the rank of a general could not fit himself in civilian life. He found his native village, which he had left as a boy, and even his own family, completely alien to his traditional concepts. Utterly disillusioned the retired general returned to his former division to die contentedly in the care of his companions-in-arms. With coldness and even cruelty, the author analyses people in a society where a utilitarian mode of life is developing to the detriment of traditional and revolutionary values.

We are now witnessing the transition of the homogenous family to the heterogenous family and the crisis of the traditional family, or simply The Family, is worrying researchers in sociology, education and psychology.