My friend Nam, a retired college professor, lives on Goldsmiths’ street, in the heart of the Old Quarter of Hanoi. An old Hanoian he feels a great deal of attachment to the good old days in the city. Whenever he drops in at my place he will inveigh against men and their behavior ever since our country shifted to a market economy: morality going downhill, proliferation of theft and smuggling, corruption of civil servants at all levels, invasion of pavements by peddles and stall-keepers, etc. In a nutshell my friend is pining for the Thang Long that Hanoi was in the past.

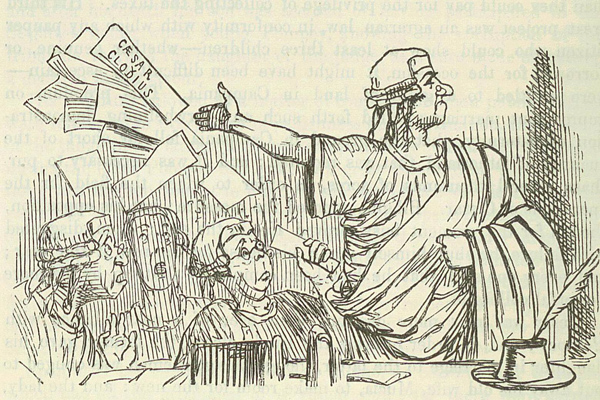

To try and comfort him. I keep repeating to him that Cicero’s angry exclamation: “O tempora! O mores! is not to be confined to the Rome of a certain period of history but could be applied to all times and all countries.

One day as I was browsing among books of ancient literature I stumbled upon an account of life in 18th century Hanoi in Pham Dinh Ho’s Vu trung tuy but (Written on A Rainy Day): it is a vivid story which makes it quite clear that thieves, crooks, and convicts were not uncommon in the “good old days”. I sent the story to Nam hoping that he would take my point. Here is a round translation of Pham Dinh Ho’s account:

‘The corporations of Dien Hung and Dong Lac are based in the streets where clothing and materials of all sorts are sold-silk, brocade, crepe…. Markets are held on the first, sixth eleventh, fourteenth, fifteenth, twenty-first, twenty-sixth, and thirtieth of each month. The market days of the Bach Ma (White Horse) corporation are very animated. The thieves use the occasion to strip people of their possessions and pick their pockets… Sometimes they pretend to be quarrelling with each other in order to create disturbances and steal packages of clothing and other goods. Sometimes they spread the rumour that elephants and horses have escaped from their keepers and are going to appear at any moment. Clients and passers-by throw their things and their purchases pell-mell and rush off jostling one another. When it is known that the rumor was false, thefts have already occurred.

“One day the wife of a great mandarin made a noisy entry into Dong Lac Corporation. She travelled in a palanquin with blinds made of painted jackdaws’ wings, preceded and followed by a swarm of lackeys and guards. She stopped her suit in front of a goldsmith’s shop then ordered her servants to ask to buy several dozen silver taels. Hardly was the haggling finished when the lady, who had remained in her palanquin, told an old servant to take ten taels to the yamen so her husband could give his opinion on the prices. The goldsmith suspected nothing. An instant later the entire escort, including the two carrier guards disappeared without warning. At sundown, as the old servant had not brought the silver back, the goldsmith went up to the palanquin to reclaim his property. Upon opening the blinds, all he saw was a dazed old blind beggar woman in a red crepe tunic who sat enthroned inside. Investigations yielded no results. The old dilapidated palanquin was worth no more than a few coins.

“These thefts and swindles can no longer be counted. The male-factors display treasures of ingenuity. It is common practice in this era of peace.”