From 1954 to the present, Vietnamese history has been affected by significant changes in politics and society. These changes are shown through Vietnam's success in the resistance war against America's invasion in 1975, which led to the liberation of the South and the unification of the country. Vietnam then advanced toward socialism and entered the renovation period with comprehensive changes in the economy, culture, society, and international integration.

After the Geneva Agreement in 1954, Vietnam was temporarily split into the North and the South. The North was totally liberated and started to build socialism while the South was invaded and dominated by American imperialists. During 1954-1955, there were big changes in the lives of Catholics in Vietnam. Large groups of parishioners in the North were enticed to join the wave of Southward migration. At that time, nearly a million parishioners and hundreds of priests moved from the North to the South of Vietnam. This not only caused negative psychology among parishioners and chaos in society but also led to a dramatic decrease in the number of priests in the North.

During 1954-1975, North Vietnam focused on stabilizing migration and mobilizing both human and financial contributions for the resistance war against America. At that time, the role of the Catholic Church was perfunctory, and its aims were directed toward serving the needs of parishioners Meanwhile, the Catholic Church in the South of Vietnam, thanks to the support of the Sai Gon government, developed in all aspects and became an important social and political force.

Generally, after 1954, Catholicism in Vietnam continued to develop as shown through the following statistics:

In I960, the population of Vietnam was approximately 21 million. This figure includes 2,096,540 Catholic followers, 23 bishops, 1,914 Catholic priests, 5,789 clergymen and 1,530 postulants.

In 1975, the population of Vietnam was 35 million, including over 3.5 million Catholic followers.

When carrying on their missionary work in Vietnam, Catholic missionaries tried to approach the ethnic minorities However, for more than two centuries in Vietnam, they could only reach the ethnic minorities in the Northwest mountainous areas and the Central Highlands. In 1876, Catholicism was introduced in the Northwest, first in Lang Son and then to Cao Bang, Bac Can, Thai Nguyen, Tuyen Quang, Ha Giang and some others. Despite their efforts, Catholic missionaries failed It) get much support from ethnic minorities in Vietnam. Up until 1954, in the whole Northwest, there were less than 100 Catholic followers, the majority of which were H'Mong people in Sa Pa - a vacation resort for the French officials and middle class at that time. Recently, the number of newly-joined Catholic followers has been increasing. According to the statistics in 2005 of the Vietnamese Catholic Church, there were 38,000 Catholic believers in the Northwest, who lived in Hung Hoa, Lang Son, Bac Ninh, Phat Diem and Thanh Hoa. In 1765, Catholicism was introduced in the Central Highlands, first in Kon Turn and then to Gia Lai, Dac Lac, Da Lat and some others. In comparison with the Northwest, the conversion rates for ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands had a better track record. In 1977, the three dioceses of ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands, including Kon Turn, Buon Me Thuot and Da Lat, had more than 100,000 Catholic followers. Later on, Catholics continued promoting missionary work and attracting more and more new followers of ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands. The statistic of the Vietnamese Catholic Church showed that up until 2005, the three dioceses in the Central Highlands had 256,910 Catholic believers from ethnic minorities out of 772,484 in the whole country, which is the equivalent of 36 percent.

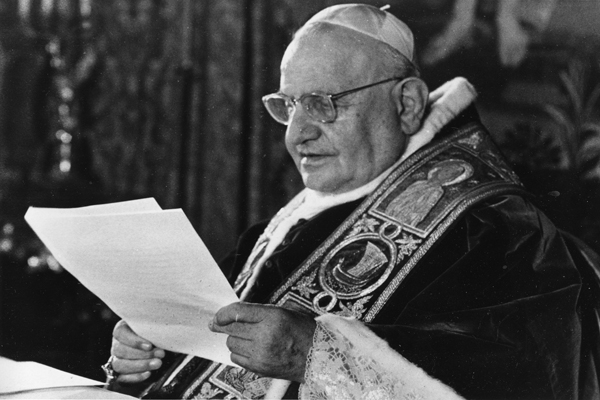

Along with the increase in numbers of Catholic followers, the Vietnamese Catholic Church improved their organization. In 1668, only four priests were Vietnamese; in 1933, after four hundred years of Catholicism in Vietnam (1533-1933), the Vatican ordained Nguyen Ba Tong as the first Vietnamese bishop. Afterwards, on November 24,1960, Pope Joannes XXIII issued an ordinance called Venarabilium Nostrorum on the establishment of Vietnamese Catholic titles and simultaneously upgraded all the bishop's palaces in the twenty dioceses from "titular palaces" to "cathedral palaces." In summary, the Vietnamese Catholic Church has experienced three periods in its history including 106 years of the protectorate (1553-1659), 300 years of apostolic prefectures (1659-1960) and 50 years of cathedral prefectures.

Many new dioceses were established in the South after 1954. Specifically, in 1955, Pope Pius XII founded Can Tho Diocese, which had been part of Phnom Penh Diocese, and put it under the management of Bishop Nguyen Van Binh. In 1957, he established Nha Trang Diocese, which had been part of Qui Nhon Diocese, and put it under the management of Bishop Marcel Piquet (also known as Loi in Vietnamese). In I960, Pope Joannes XXIII founded Long Xuyen, which had been part of Can Tho Diocese, and assigned Bishop Nguyen Khac Ngu to manage it. That year, he also established the dioceses of Da Lat and My Tho, which were formerly part of Sai Gon Diocese, and put them under the management of Bishop Nguyen Van Hien and Bishop Tran Van Thien respectively. In 1963, Pope Joannes XXIII separated Qui Nhon Diocese managed by Pham Ngoc Chi from Da Nang Diocese. In 1965, Pope Paulus VI separated Xuan Loc Diocese under the management of Bishop Le Van An and Phu Cuong Diocese under the management of Bishop Pham Van Thien from Sai Gon Diocese. In 1967, he continued to separate Buon Ma Thuot Diocese managed by Bishop Nguyen Huy Mai from Kon Turn Diocese. In 1975, he separated Phan Thiet managed by Bishop Huynh Van Nghi from Nha Trang Diocese. By 1975, there were a total of twenty-five dioceses in three Vietnamese archdioceses, which are still in operation today. They include:

Sai Gon Archdiocese, including nine dioceses: Sai Gon, Vinh Long, Can Tho, My Tho, Long Xuyen, Da Lat, Xuan Loc, Phu Cuong, and Phan Thiet. Hue Archdiocese, including six dioceses: Hue, Qui Nhon, Nha Trang, Kon Tum, Da Nang, and Buon Me Thuot. Hanoi Archdiocese, including ten dioceses: Hanoi, Hung Hoa, Bui Chu, Phat Diem, Bac Ninh, Hai Phong, Thai Binh, Thanh Hoa, Vinh, and Lang Son.

By 2005, there were 5.9 million Catholic followers, 91 bishops, 2,281 priests, 13,254 clergymen of 60 orders (including 60 international orders), 5,100 churches, and chapels of 25 dioceses, and 2,100 parishes in Vietnam. During this time, the Vietnamese Catholic Church officially established six major seminaries, including:

Saint Joseph Major Seminary (Hanoi), established in 1971 on the foundation of Saint Joan Minor Seminary (1954) and supposed to train postulants for eight dioceses: Hanoi, Hai Phong, Hung Hoa, Phat Diem, Bui Chu, Bac Ninh, Thai Binh, and Lang Son;

Hue Major Seminary, established in 1994 on the foundation of Hue Seminary (1962) and supposed to train postulants for three dioceses: Hue, Kon Tum, and Da Nang; Vinh-Thanh Major Seminary, established in 1988 on the foundation of Xa Doai Major Seminary (Nghe An) and supposed to train postulants for two dioceses: Vinh and Thanh Hoa; Sao Bien (Starfish) Major Seminary (Nha Trang), established in 1991 and supposed to train postulants for three dioceses: Nha Trang, Qui Nhon and Ban Me Thuot; Saint Joseph Major Seminary (Ho Chi Minh City), established in 1986 on the foundation of Saint Joseph Seminary (1886) under the management of Bishop Miche and supposed to train postulants for six dioceses: Sai Gon, Phu Cuong, My Tho, Xuan Loc, Phan Thiet and Da Lat (Xuan Loc Sub- seminary of Ho Chi Minh City Major Seminary was established in 2006); and Thanh Qui Major Seminary (Can Tho), established in 1988 and supposed to train postulants for three dioceses: Can Tho, Vinh Long, and Long Xuyen. According to the statistics of the Vietnamese Catholic Church in 2005, these six major seminaries had 1,217 postulants and 1,764 candidates for postulancy. A total of 202 postulants had graduated.

After the liberation of the South, there occurred an important event that marked the development of the Vietnamese Catholic Church. From April 24 to May 1, 1980, all the bishops in Vietnam convened in Hanoi for the establishment of the Vietnamese Bishops' Council. It consisted of all the bishops who were working in Catholic dioceses in Vietnam. Its duty was to "encourage joint efforts to promote the good deeds offered to God through monkhood and appropriate methods in accordance with the context of the era and in the spirit of attachment to the nation and the country."

The Executive Committee of the Vietnamese Bishops' Council IN not restricted in terms of membership and includes the following titles: a chairman, one or more vice-chairmen, a general secretary, and one or more deputy general secretaries. (A deputy general secretary may be a priest.) The Executive Committee is assisted by nine commissions under the management of bishops.

They include:

- Bishops' Commission on Teachings and Beliefs,

- Bishops' Commission on Worship,

- Bishops' Commission on Holy Music and Arts,

- Bishops' Commission on Priests and Postulants,

- Bishops' Commission on Clergymen,

- Bishops' Commission on Parishioners,

- Bishops' Commission on Holy Writ,

- Bishops' Commission on Culture, and

- Bishops' Commission on Evangelization.

Each term of the Vietnamese Bishops' Council lasts for three years. Since its establishment in 1980, the Vietnamese Bishops' Council has experienced ten terms: the first term (1980-1983), the second term (1983-1986), and the third term (1986-1989) were chaired by Cardinal Trinh Van Can; the fourth term (1989- 1992) and the fifth term (1992-1995) were chaired by Bishop Nguyen Minh Nhat; the sixth term (1995-1998) and the seventh term (1998-2001) were chaired by Cardinal Pham Dinh Tung; the eighth term (2001-2004) and the ninth term (2004-2007) were chaired by Bishop Nguyen Van Hoa; the tenth term (2007-2011) was chaired by Bishop Nguyen Van Nhon.

After its founding, the Vietnamese Bishops' Council sent a letter called Common Letter 1980 to all Catholic priests, clergymen, and parishioners throughout the country. In addition to information about the Nationwide Bishops' Congress and the new direction of the Vietnamese Catholic Church, the letter highlighted the Catholics' responsibility and sentiment toward the nation: “For Catholic followers, love for the nation and compatriots arises both from genuine affection and from the requirement of Evangelicalism." At the same time, the letter laid down the plan to build the so-called Holy Society of Jesus in Vietnam to help build up and protect the nation. It reads: "As the Holy Society in the heart of the Vietnamese nation, we are determined to identify ourselves with the fate of the country and follow our national tradition to mix with the present life of the country. The Council has taught us that we should advance together with all mankind and share the same secular fate with the world. Therefore, we should progress and share the same fate with our nation. We are invited by God to become His children. This country is the mother's heart where we are supported to realize His invitation; this nation is the community given to us by God to fulfill our duties as both citizens and God's children .. Live the Gospel among the nation."

The letter also assigned the duty to build a new Catholic lifestyle and a belief that still respects the national tradition.

In the following congresses, the Vietnamese Bishops' Council issued common letters and notices, depending on specific topics, to concretize the course of social activities of the Vietnamese Catholic Church as follows:

The Second Congress (1983) of the Vietnamese Bishops' Council issued a letter of religious duties on the topic "Redemption Year." After affirming the spirit of the Common Letter 1980, this letter appeared: "Brothers and sisters, read the Common Letter 1980 of the Vietnamese Bishops' Council again. That letter brought us faith and excitement and helped us obtain satisfactory achievements both in our religious and secular lives. We should keep advancing on the way we chose, namely spreading the gospel among the nation for their happiness." The Third Congress (1986) of the Vietnamese Bishops' Council took place in 1986 when the country entered the renovation period. This congress issued a notice that clearly stated the Catholics' responsibility as follows: "In the duty of building and protecting the country, we should make every effort to make more and more contributions, especially in the present context of the country ... We are both Catholics and citizens of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. These two roles will not contradict each other if each of us leads an actual religious life and has a sincere love for the country." The Fourth Congress (1989) issued a common letter with the topic "Unification." The letter asserted: "We have so many things to do for the Church and the country ... first and foremost promoting the healthy lifestyle in the spirit of the Gospel and national traditions." The common letter of the Fifth Congress (1992) focused on the integration with the national culture. It reads: "Looking for the national cultural identity does not purely mean taking back ancient values, but it means expressing national characteristics in rituals, everyday life, and theological thinking and language." The common letter of the Sixth Congress (1995) raised the Catholics' responsibility in social issues: "Actively block all the canals whose water is contaminated. Join efforts to help the poor build at least bamboo or thatched houses. Build classes for homeless children. Jesus' serving spirit should be the spirit of everyone and each Catholic." The common letter of the Seventh Congress (1998) focused on the ethical issues in the process of cultural integration. It reads: "Love and unification is the typical feature of Jesus Christ's Gospel and the deepest meeting point of the Gospel and Vietnamese culture, whose morality is founded on compatriotism and loyalty." The common letter of the Eighth Congress (2001) appealed to Catholics: "To love and serve, we must, first and foremost, continue to stand side by side with our nation, sympathize with them and share their hope and pursuit for promotion. We do not view economic, political, social and educational issues as outsiders, but we should consider them as ours and actively make contributions to solving them so that everybody can live a prosperous life." The common letter of the Ninth Congress (2004) expressed the Catholics' open attitude toward other religions and the cultural variety in Vietnam. It appealed Catholics to "be aware of the variety of cultures and religions, be open to other religions, and actively cooperate with their followers and those who are enthusiastic in charity and social work." The common letter of the Tenth Congress (2007) discussed the education of Christianity in the Vietnamese cultural traditions. It reads: "Our people are always proud of our traditional fondness for learning and respect for teachers and moral standards. In the past, those traditions contributed to enriching the Vietnamese culture and generating well- known individuals who glorified our country. Nowadays, those traditions must become one of the criteria of the education of Christianity in Vietnam."

Thus, in the new regime, especially since the establishment of the Vietnamese Bishops' Council (1980), the Vietnamese Catholics have identified the new direction of their work as follows: striving for advances and integration in the national community as well as joining efforts to build up a peaceful, prosperous and happy life.

Another important issue in the life of the Vietnamese Catholics in the new regime is their relation with the Vatican. After the victory of the August Revolution, the Government of Vietnam still accepted the organizational relationship between the Vietnamese Catholic Church and the Vatican. The Decree Number 234/SL- NN, which was signed and promulgated by President Ho Chi Minh on June 14, 1955, clearly stated: "The Government will not interfere in the internal issues of religions. As for Catholicism, the religious relationship between the Vietnamese Catholic Church and the Holy See is an internal matter of the religion."' Therefore, the religious activities such as going to Rome to attend the Pope's audience and visit the tombs of apostles Pius and Paulus (Ad Limina), participating in the Synod, and receiving titles and ranks from the Vatican for bishops, general bishops, cardinals, and others are still held normally by Vietnamese bishops. Since 1989, together with the national renovation cause and the extension of international cooperative relations, the relationship between the Government of Vietnam and the Vatican has been promoted through periodic mutual visits for the discussion of issues of common concern. On July 1, 1989, Cardinal Roger Etchagaray, representative of Pope Jonannes Paulus II, paid a visit to Vietnam. This visit marked the beginning of the State- level relationship between the Government of Vietnam and the Vatican. Accordingly, there are annual meetings between the representatives of the Government of Vietnam and the Vatican, either in Vietnam or the Vatican, for discussions and exchanges. By 2009, there were eighteen meetings between the Government of Vietnam and the Vatican, two of which took place in Vietnam and sixteen at the Vatican. On January 25, 2007, the Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung paid a visit to the Vatican and had a talk with Pope Benedictus XVI. This visit marked a new development in the relation between the two sides. In this visit, the Vietnamese Prime Minister delivered a speech on the relationship between Vietnam and the Vatican.

When invading Vietnam, both French colonialists and American imperialists tried to make use of Catholicism to do their groundwork. Their words, which aimed at separating Catholics from the national revolution, could deceive only a part of Catholic followers and priests, as most Catholics still had patriotic feelings. Throughout history, Vietnamese revolutions and patriotic campaigns have always attracted the active participation of large numbers of parishioners, priests, and clergymen. For instance, under the Nguyen Dynasty, some Catholic priests and parishioners like Nguyen Truong To (1828- 1871), Truong Vinh Ky (1837-1898), Priest Nguyen Van Tuong (1852-1917), Nguyen Than Dong (1886-?), Priest Dau Quang Linh (1870-1941), Le Khanh (1886-1910) and Mai Lao Bang (1870-1942) were well-known for their great patriotism.

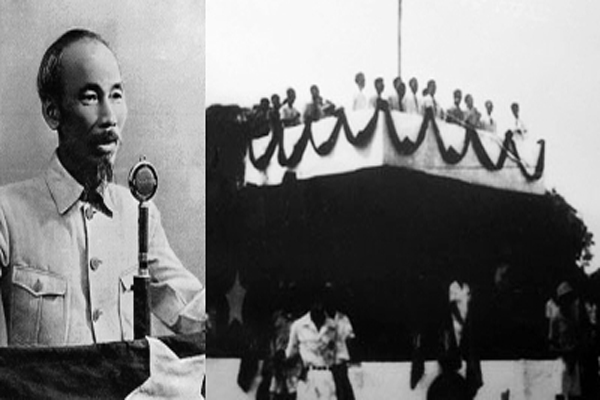

After the victory of the August Revolution in 1945, President Ho Chi Minh delivered the Declaration of Independence on September 2, 1945. Bishop Nguyen Van Tong and three other bishops, who were representatives of all the Catholics in Vietnam at that time, sent a message to Pope Pius XII, calling for the Pope's support for Vietnam's independence. It reads: "We, the faithful, would like to pay great honor to the Father and pray that you confer your benediction and tolerance for the independence that we have won and are determined to protect at all costs."

At the end of September 1945, the four Vietnamese bishops sent a second message to the Catholic world, calling for their support to Vietnamese independence.

Many Catholic patriotic personalities and intellectuals supported and joined the August Revolution (1945) and the anti- American resistance war (1954-1975) in different ways. Typical examples included Nguyen Van Ha (then Minister of Culture), Vu Dinh Tung (then Minister of Social Affairs), priests Ho Thanh Bien, Vu Xuan Ky, Vo Thanh, Nguyen The Vinh, and Pham Quang Phuoc.

During the anti-American resistance war, tens of thousands of Catholic youth joined the army to fight against the enemy troops in the South. Many of them later became revolutionary heroes, martyrs, and wounded soldiers. Many Catholic villages and communes became historical places. Typically, Nghe An Province alone had 197,658 youth joining the army (out of which 305 later became revolutionary martyrs and 264 wounded soldiers) and 5 Vietnamese heroic mothers. Ha Nam Ninh Province (now divided into provinces of Ha Nam, Nam Dinh, and Ninh Binh) had a total of 6,984 revolutionary martyrs and 3,042 wounded soldiers. The title of the Hero of the People's Armed Forces was awarded to six Catholic individuals (including Tran Van Chuong, Khuc Van Luong, Do Van Chien, Pham Quang Hanh, Nguyen Van Hieu, and Nguyen Thi Nho) and three Catholic communes (including Kim Dai in Ninh Binh Province, Hai Thinh in Nam Dinh Province and Quang Khue in Quang Binh Province).

Patriotic movements involving Vietnamese Catholics led to the establishment of a patriotic Catholic organization called the Liaison Committee for Patriotic and Peace-loving Catholics (shortly known as the Nationwide Catholic Liaison Committee) in 1955. Since 1983, it has been known as the Vietnam Committee for Patriotic Catholic Solidarity (shortly known as Vietnam Committee for Catholic Solidarity).

The aforementioned organization and some other patriotic organizations of the Catholics were born in special conditions. Shortly after the Declaration of Independence was made public (September 2, 1945), the French colonialists returned to Vietnam, and the Vietnamese people had to start their prolonged resistance war against the French. Catholic resistance organizations such as the South Catholic Resistance Society whose key cadres included priests Ho Thanh Bien and Vo Thanh Trinh and the Catholic Resistance Liaison Committee whose key cadres included priests Vu Xuan Ky, Nguyen The Vinh, and Pham Quang Phuoc were founded to mobilize Catholics to participate in the resistance war and national construction. The Catholic patriotic organizations published the two newspapers, namely Vi Chua vi To quoc (For Jesus and for the Homeland) in the South and Sang danh Chua (Bringing Honor to God) in the North, to popularize and promote patriotism among Catholics.

In the early 1950s, the Catholic patriotic organizations found it necessary to unify all the Catholic resistance organizations and establish a nationwide organization to improve the practicality and efficiency of patriotic activities. In August 1953, the National Catholic Conference was held in Viet Bac (Northernmost Vietnam) base. The Conference gathered Catholic representatives and dignitaries from different localities throughout the country. All the participants discussed and reached an agreement on the unification of all Catholic resistance organizations. For difficulties in traveling, representatives of Catholic priests and parishioners could not attend the Conference, so the plan was not realized.

After the signing of the Geneva Agreement (1954), the American imperialists and Sai Gon Government incited and organized big migrations of Catholics from the North to the South, which caused heavy social consequences. In that situation, it was necessary to establish a nationwide Catholic patriotic organization. A mobilizing committee including Catholic priests and intellectuals who were representatives of Catholic patriotic movements and organizations in the three regions of Vietnam was founded and headed by Priest Vu Xuan Ky. After three months of preparation with active campaign activities, from March 8-11, 1955, the Meeting of Representatives of Patriotic and Peace-loving Catholics was held in Hanoi. The Meeting gathered 191 delegates, including 46 priests, 8 clergymen (5 females and 3 males), and 137 representative parishioners.

The Meeting discussed and decided to establish the Liaison Committee for Patriotic and Peace-loving Catholics (shortly known as the Nationwide Catholic Liaison Committee). The Committee had 27 members, including 11 priests. Priest Vu Xuan Ky was nominated Chairman; Priest Ho Thanh Bien and lawyer Duong Van Dam were appointed Vice-chairmen. The Meeting also approved the Committee's Regulations, which included eight clauses.

The Committee's mission was to gather all Catholics, who respect God and love their homeland, and encourage them to stand side by side with their compatriots to fulfill the following tasks:

Raising the respect for God and love for the homeland among Catholics; Cooperating with the nationwide people to fight for sustainable peace and unify the country through free general election as favorable conditions for the achievement of independence and democracy throughout the country; and Uniting with people nationwide to crush the imperialists' plot to make corrupt use of the religion to undermine the country. The Committee published the newspaper Chinh Nghia (Justice) on the foundation of the former ones, Vi Chua vi To quoc (For Jesus and for the Homeland) in the South and Sang danh Chua in the North.

After the Spring 1975 victory, the patriotic movements of Catholics underwent positive changes. Along with the activities of the Committee, some Catholic localities also carried out patriotic movements and implemented economic and social tasks simultaneously. In Ho Chi Minh City, patriotic movements developed dramatically and resulted in the birth of Ho Chi Minh City Committee for Catholic Mobilization in 1980. In order to unify nationwide patriotic activities and meet the aspiration of Vietnamese Catholics, the Nationwide Catholic Liaison Committee held an open meeting in December 1981 which suggested convening a national Catholic representative congress to set up an organization of nationwide Catholic patriotic movements. In November 1983 in Hanoi, the Congress of Vietnamese Catholic Representatives for National Construction and Defense founded the Vietnam Committee for Patriotic Catholic Solidarity (later renamed Vietnam Committee for Catholic Solidarity) and approved the regulations of the newly-established committee. The Congress also confirmed that the Vietnam Committee for Catholic Solidarity was descended from preceding organizations of Catholic patriots' movements.

The Congress also decided to replace Chinh Nghia with the weekly newspaper Nguoi Cong giao Vietnam (The Vietnamese Catholic) as the official organ of the Vietnam Committee for Catholic Solidarity and maintained the newspaper Cong giao va Dan toc (Catholicism and Nation) published by the Ho Chi Minh City Committee for Catholic Solidarity as the means to popularize the principle, goal, and course of action of the Vietnam Committee for Catholic Solidarity.

By 2008, the Vietnam Committee for Catholic Solidarity had held five congresses, respectively in November 1983, October 1990, December 1997, March 2003, and November 2008.

It was laid down that the organizations of the Vietnam Committee for Catholic Solidarity would be set up in the central provinces and provinces under the central government, where great numbers of Catholics settle. In 2008, a total of 37 municipal and provincial committees for Catholic solidarity were established in Vietnam. They all had representatives taking part in the Vietnam Committee for Catholic Solidarity and aimed to realize its principle and goal.

To make bright pages in the national history, the Vietnamese Catholics have been imbued with patriotism and tried all efforts to overcome all obstacles left by the past history and reach an agreement with the national revolution, the Fatherland, and humanism. It was Catholics' patriotic activities that created significant premises for the building of the direction "Live the Gospel among the Nation" written in the famous Common Letter 1980 as well as in the later common letters of the Vietnamese Bishops' Council.