In 1858, the French-Spanish allied troops started to attack Da Nang, beginning the invasion of Vietnam by Western capitalism. With the Quy Mui Peace Treaty in 1883, and the Patenotre Treaty between the Hue Court and French colonialists.

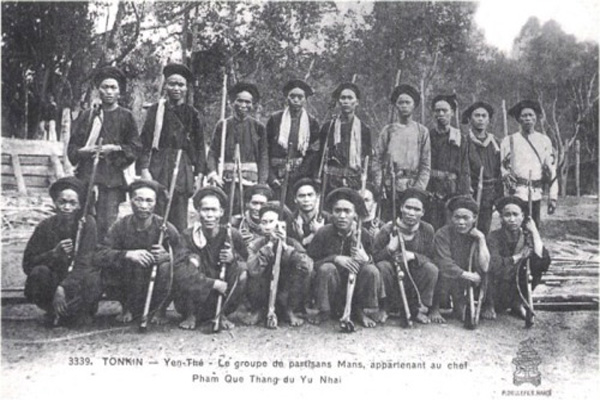

In 1884, Vietnam was divided into three parts and dominated by the French. In the wake of French colonialization for nearly a century, the Vietnamese people did not resign themselves to being slaves but instead revolted against the invaders. There were famous uprisings such as the Truong Dinh uprising (1859-1864), the Nguyen Trung Truc uprising (1861-1868), the Ba Dinh uprising (1886-1887), the Bai Say uprising (1885-1889), the Hung Linh uprising (1886-1892), the Huong Khe uprising (1885 - 1896) and the Yen The uprising (1887-1912). By the early twentieth century, there were a few bourgeois-orientated national liberation movements such as Dong Du (Going East) and Duy Tan (Reform). However, the uprisings, the movements were either bloodily repressed or failed.

A significant event in Vietnamese history in the twentieth century was the birth of the Communist Party of Vietnam In 1930 which put a stop to the crisis in revolutionary policy lines and revolutionary leaders in Vietnam. The Communist Party of Vietnam unified the people and led the revolution to victory. The first success was the August Revolution in 1945, which founded the first democratic government in Southeast Asia. The next was the fight against the French colonialists which finished with the historical Dien Bien Phu campaign in 1954. After 1954, the country was divided into two parts with two strategic missions, to build socialism and to fight against the American imperialists to complete the democratic national revolution. In 1975 with the historical Ho Chi Minh campaign, the Vietnamese people achieved total and absolute success in the great resistance against the American invaders. Vietnamese history entered a new stage of development - the stage of independence, unity, and movement toward socialism.

As mentioned above, Buddhism in Vietnam fell into decline under the early Le Dynasty. Later it grew again but was not as strong as before. In general, Buddhism in Vietnam continued to decline until the 1920s when the movement to ameliorate Buddhism became more boisterous and deeper in all aspects.

In fact, in the early twentieth century, the movement to ameliorate Buddhism was not limited to Vietnam but was happening in many other countries as well. Great changes in the economy, society, ideology and the decline of Buddhism, in general, served as catalysts for the movement which started in China and Japan, and then spread to many countries in Asia, with the mottoes "Revolution in the doctrine," "Revolution in the rules" and "Revolution in the sangha." Vietnamese Buddhist supporters were encouraged greatly by the movement in China when they learned of it through writings, particularly the magazine Hai Chao Yin, and the enthusiastic efforts of Venerable Superior Tai Xu. In addition to spiritual and religious importance, Buddhism in Vietnam had positive socio-political significance related to the struggle for national liberation. During the early decades of the twentieth century, the national liberation revolution in Vietnam fell into deep crises of revolutionary policy lines and leaders. Some monks and patriotic intellectuals wanted Buddhism to develop so that the country could be united under the Buddhist flag to fight against the French invaders and win liberation for Vietnam.

The movement to revitalize Buddhism began in Sai Gon and some southern provinces in 1920 with the participation of monks such as Khanh Hoa (1878-1947) and Thien Chieu (?-?). From the South, it spread to the Center and the North with the participation of Venerable Superior Giac Tien, Superior Monks To Lien, Tri Hai, and laymen Le Dinh Tham, Nguyen Nang Quoc, Phan Ke Binh, Tran Van Giap, Nguyen An Ninh, Huynh Thuc Khang, Bui Ky, and Nguyen Trong Thuat. The movement lasted until the mid-1950s and made some important achievements.

First, Buddhism began to operate organizationally, which was different from the loose operations in the past. Buddhist organizations were established in the three regions, among which there were six important ones. They included:

Two Associations in the South

Cochinchine Association for Buddhist Studies founded by Venerable Superior Khanh Hoa in 1930 (in 1951, layman Mai Tho Truyen re-named it South Vietnam Buddhist Studies Association);

South Vietnam Sangha founded in June 1951.

Two Associations in the Center:

An Nam Association for Buddhist Studies founded by layman Le Dinh Tham in 1932;

Central Vietnam Sangha founded in 1949.

Two Associations in the North:

Tonkin Buddhists' Association founded by layman Nguyen Nang Quoc in 1934;

North Vietnam Buddhist Clergy Rectification Association founded by Superior Monk To Lien in 1949 (in 1950, it was renamed North Vietnam Sangha).

In the wake of the establishment of Buddhist organizations, Buddhist books were collected, translated, and printed for wider distribution. Various magazines emerged to facilitate the improvement of Buddhist studies. Thus, Cochinchine Association for Buddhist Studies introduced the magazine Tu Bi am (Sounds of Compassion) in 1931; An Nam Association for Buddhist Studies published the magazine Vien am (Perfect Sound) in 1932; the Tonkin Association for Buddhist Studies published the magazine Duoc tue (Wisdom Torch) in 1934; the Ch'an Association published the magazine Bat Nha am (Prajana Sound) in 1931; Luong Xuyen Buddhist Studies published the magazine Duy tam Phat hoc (Idealistic Buddhist Studies). These magazines conveyed many hot debates, discussions, and exchanges of views on the issues of contemporary Buddhism, Buddhist history, and Buddhist studies, which drew the attention of Buddhists, scholars, and the public in general and gave an impetus to the movement of rejuvenating Buddhism. Monk Thien Chieu strongly supported the renewal of Buddhism through his numerous articles for magazines and his books. Thus, while working as chief-editor for the bulletin Phat hoa tan thanh nien (Rejuvenating Buddhism), he compiled the series on Buddhist Studies (Phat hoc tung thu) and published such books as Phat hoc van dap (Buddhism: Questions and Answers), Cai thang Phat hoc (The Ladder in Buddhist Studies), Phat giao vo than luan (An Essay on Buddhist Atheism), Phat hoc tong yeu (Essentials of Buddhism), Chan ly Tieu thua va chan ly Dai thua (Truths of Hinayana and Mahayana), Kinh Phap cu (Dharmapada Sutra) and Kinh Lang nghiem (Surangama Sutra).

An important event in the history of Vietnamese Buddhism, and the result of the movement to ameliorate Buddhism, occurred in 1951 in Hue: the regional Buddhism organizations gathered to establish the General Association of Vietnamese Buddhism. This was considered to be the first campaign for uniting Buddhists in Vietnam. The Chairman of this Association was the Venerable Superior Thich Tinh Khiet; the Vice-Chairman was Superior Monk Thich Tri Hai. The headquarters of the Association was at the Tu Dam Pagoda, Hue. Although it was founded in 1951, the Association was not recognized by the Government until 1953. It did not have real power over the member associations, so in reality, their activities were limited to monasteries. Therefore, in September 1952, representatives of sanghas in all three regions held a congress at the Quan Su Pagoda, Hanoi to found the National Buddhist Sangha Congregation with the aim of helping the General Association of Vietnamese Buddhism establish united leadership for Buddhist activities and create a relationship with worldwide Buddhist organizations, including the World Friendship of Buddhists (WFB), which had just been founded with Vietnam as one of the founders. Venerable Superior Thich Hue Tang was proclaimed the superior leader, Superior Monk Thich Tri Hai the chief executive manager, and Superior Monk Thich To Lien the general secretary. Subordinate to the Congregation was the Section for Ritual, Section of Training, Section for Membership, and Section for Enforcement of Rules.

Along with consolidation and maturity in the organization, the movement to ameliorate Buddhism also built Buddhist training centers in the three regions. In the South, there were the Clergy Training School in Cho Lon; some Buddhist classes in the Tuyen Linh Pagoda (Ben Tre), Phi Lai Pagoda (Chau Doc), Giac Hoa Pagoda (Bac Lieu), Long Hoa Pagoda (Tra Vinh) and Thien Phuoc Pagoda (Vinh Long); Luong Xuyen Buddhist School (1935); and Sakyamuni School (1935). In the Central region, there was the Elementary School for Buddhist Clergy (1935), the Buddhist Intermediate School in Binh Dinh (1937), the Truc Lam and Tay Thien Buddhist Schools (1935), and the Bao Quoc and Kim Son Buddhist Schools (1935). In the North, there were two primary classes in Phuc Yen and Hai Duong for monks and nuns, the Buddhist Intermediate School in the Quan Su Pagoda (Hanoi) and the Buddhist College in the So Pagoda (Ha Dong).

During the movement to revitalize Buddhism, the French colonialists tried in many ways to draw religious forces, for their own political goals, including some Buddhist organizations and personalities. However, the majority of monks and nuns held to patriotic traditions and showed a strong attachment to the people. They actively contributed human and material resources to the August Revolution in 1945, and the resistance against French colonialists from 1945 to 1954. Most of the monks, nuns, and Buddhist followers took part in the Viet Minh and Lien Viet Fronts at different levels. Many pagodas became bases or shelters for revolutionaries. In the South, the Buddhist Association for National Salvation attracted many monks and nuns to patriotic activities.

After the year 1954, Vietnam was divided into two parts. Consequently, the developments of Buddhism in the two parts were not the same.

In September 1957, some representative monks and nuns in the North carried out a campaign to establish a new organization. In March 1958, Buddhists in the North organized a congress with the participation of over 200 monks, nuns, and Buddhist followers to establish the Unified Vietnamese Buddhist Association. The aims of the Association were to gather the clergy, laity, and scholars to propagate Buddhist doctrine for people's benefit, serving the country and keeping the peace. Venerable Superior Thich Tri Do was the chairman, Venerable Superior Thich Duc Nhuan and scholar Minh Tam Le Dinh Tham were the vice-chairmen.

Since its founding, the Unified Vietnamese Buddhist Association took an active part in religious and social affairs and in patriotic movements. It has also encouraged followers, monks, and nuns to support and contribute to the cause of building and protecting socialism in the North, fighting against the American imperialists to liberate the South and unify the country. It was a member of the Asian Buddhist Conference for Peace (ABCP) and enthusiastically took part in international antiwar and peace activities. It can be said that the establishment of this Association was an important advancement in the course of the development of Buddhism in the North attached to national development.

In the South, during the period of 1954-1975, Buddhism changed greatly; many Buddhist organizations and sects and denominations were founded. Up to 1975, there were dozens of Buddhist organizations such as the Unified Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation (1964), Khmer Hinayana Buddhism, Mendicant Monks Sangha (founded by Minh in 1940), Association of Pure Land Laity (founded by Mr. Nguyen Van Bong in 1933), Theravada Buddhism (founded by Nguyen Van Giang in 1945), Ancient Monastery (1952), Pure Land Buddhism (founded by 1955), Vietnamese Association of Buddhist Studies, Lin Ji Ch'an Sect, Meditation Bodhimandala, T'en Tai Teaching and Meditation Sect, and Kwan Yin Universal Salvation.

Among these organizations and sects, we should mention the founding of the Unified Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation. The General Buddhist Association (founded in 1951 in Hue) called upon monks and Buddhist followers to resist the suppression and persecution of Buddhism by the dictatorial government of Ngo Dinh Diem in the early 1960s. The result was the set up of the Joint Committee for Buddhism Protection in 1963 by 11 Buddhist organizations: Vietnam General Buddhist Association; Theravada Sangha Congregation, Central Vietnam Sangha Congregation, Meditation Bodhimandala Congregation, Vietnamese Sangha Congregation, North Vietnam Sangha Congregation, Theravada Buddhism Association, South Vietnam Buddhist Studies Association, Central Vietnam Buddhism Association, and Vietnamese Buddhism Association. On December 31, 1963, they held a congress to establish the Unified Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation. In early 1964, the Congregation approved its Charter and proclaimed Thich Tinh Khiet to be Tang thong and established two leading organs, the Sangha Council and the Dharma Council.

After some time in operation, the Unified Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation began to be split. In 1966, it was divided into two sectors. The first was led by Superior Monk Thich Tam Chau with its headquarters at Vietnam Quoc Tu pagoda, called the Unified Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation Vietnam Quoc Tu Sector. The other had their base in An Quang pagoda and was called the Unified Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation An Quang Sector.

The Unified Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation Vietnam Quoc Tu Sector existed only for a short time as it was isolated and self-destructed because some of its activities were against the desires of the monks and nuns.

The Unified Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation An Quang Sector continued operating until the early 1970s when some internal divergences arose. This situation lasted until the liberation of the South in 1975.

During its operation, the Unified Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation was structured with five levels: central, regional, provincial, communal, and grassroots levels.

The leading organs were the Sangha Council and the Dharma Council. At the Dharma Council, there were specialized agencies including the Section for Sangha Affairs, Section for Propagation of Faith, Section for Rites, Section for Finance and Construction, Section for the Laity, and the Youth Section. At the regional level, there were seven divisions named after famous monks including Van Hanh (Northern part of the Central Delta), Lieu Quan (Southern part of the Central Delta), Khuong Viet (Central Highlands), Khanh Hoa (Eastern part of the South), Hue Quang (Western part of the South), Vinh Nghiem (Northern Buddhist followers), and Quang Duc (Sai Gon, under the Dharma Council).

For a long time, the trend of modernization dominated Buddhism in the South. Buddhist sects and denominations made every effort to consolidate their organization. They opened training schools; intellectualized monks and nuns; enlarged Buddhist societies; and built pagodas, temples, and economic, cultural, and social bases. This resulted in a prosperous development of Buddhism which had ever been recorded in Buddhist history over the centuries. The Americans and Saigon administration tried to promote and control this process with the aim of keeping monks, nuns, and Buddhist followers from the revolution, and ensure security and balance with Catholicism within the framework of their scheme to take advantage of religions for their benefit.

Between 1954 and 1975 in Southern urban areas, there was a struggle against American imperialists and the Saigon government by Buddhist followers. In the early 1960s, the ebullient struggle movement of Buddhists contributed to the collapse of the dictatorial regime of Ngo Dinh Diem.

During this period, some monks and Buddhist followers bravely committed self-immolation to oppose American imperialists and the Saigon government, and to defend "the Dharma and the Nation." They included Thich Quang Duc (on June 11, 1963), Bhandanta Thich Nguyen Huong (on August 4, 1963), Bhandanta Thich Thanh Tue (on August 13, 1963), nun Thich Nu Niem Quang (on August 15, 1963), Thich Tieu Dieu (on August 16, 1963), Buddhist Quach Thi Trang (on August 25, 1963), Bhandanta Thich Quang Huong (on October 5, 1963), Bhandanta Thich Thien My (October 27, 1963), Buddhist Dao Yen Phi (on January 26, 1965), Bhandanta Thich Thien Tue (on June 1, 1966), Thich Nu Thanh Quang (on May 26, 1966) and Buddhist Nhat Chi Mai (on May 16, 1967). They are examples embedded in the history of Vietnamese Buddhism and national history.

The reality of Buddhism during 1954-1975 shows that, whenever Buddhism has a strong attachment to the national and national tradition, it has power; however, when it diverges from the traditions of patriotism-cum-self-perfection, it becomes neglected and it inevitably declines. While a small proportion of Buddhists in the south were affected by negative trends, most monks, nuns, and Buddhists stood by the nation, supported and took part in the revolution. It was the exertions and contribution of Buddhists that helped Buddhism retain its influence on the people.

In the wake of the great victory in the spring of 1975, Vietnam enjoyed peaceful independence and unification, which helped Buddhists unite all Buddhist sects and denominations into one organization. In February 1980, the Canvass Committee for Buddhist Unification was founded with 33 monks, nuns, and laypeople, who represented Buddhist sects and denominations, from around the whole country. The President of the Committee was Venerable Superiors Thich Tri Thu and the standing vice presidents included most venerable monks Thich The Long, Thich Minh Nguyet, Thich Tri Tinh, Thich Buu Y, Thich Mat Hien, and Thich Gioi Nghiem. Its operation was under the direction of the Sangha Committee, which included Venerable Superiors Thich Duc Nhuan, Thich Thanh Duyet, Thich Phap Trang, and Thich Hoang Thong, among others. After two years of preparation, in November 1981, a congress for unifying Buddhist associations and denominations was held in Hanoi with the participation of 165 monks, nuns and laypeople from nine congregations in the country.

1. The Unified Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation had twenty-two delegates led by Venerable Superior Thich Thien Sieu.

2. The United Vietnamese Buddhist Association had twenty- three delegates led by Venerable Superior Thich Nguyen Sinh.

3. Vietnamese Traditional Buddhist Congregation had twelve delegates led by Venerable Superior Thich Tri Tan.

4. Ho Chi Minh City Buddhism Liaison Committee had ten delegates led by Venerable Superior Thich Thien Hao.

5. Vietnamese Therevada Sangha Congregation had seven delegates led by Venerable Superior Thich Sieu Viet.

6. Western South Vietnam Association for Solidarity of Patriotic Monastics had eight delegates led by Venerable Superior Duong Nhon.

7. Vietnamese Mendicant Sangha Congregation had six delegates led by Venerable Superior Thich Giac Nhu.

8. Thien Thai Teaching and Meditation Sect had five delegates led by Venerable Superior Thich Dat Phap.

9. Vietnamese Buddhist Studies Association had six delegates led by layman Tang Quang.

Congress set up the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation, approved the Charter and Action Program under the motto "Dharma - Nation - Socialism" and elected the Sanga Council including fifty venerable superiors, and the Executive Committee including fifty monks, nuns, and representative laypeople. The Chairman of the Sangha Council in the first tenure was Venerable Superior Thich Duc Nhuan; the Vice-Chairmen included Venerable Superiors Thich Don Hau, Thich Minh Nguyet, Thich An Lam, Maha Sarey, Thich Mat Hien, Thich Hue Thanh, and Thich Nguyen Sinh. The Chairman of the Executive committee in the first tenure was Venerable Superior Thich Tri Thu and Vice-presidents were Venerable Superiors Thich The Long, Thich Tri Tinh, Thich Thien Hao, Thich Thanh Chan, Thich Buu Y, Thich Gioi Nghiem, Thich Giac Nhu, Chau Mun, and Superior Monk Thich Minh Chau.

The unification of the Buddhist associations and congregations was a very important event in the history of Vietnamese Buddhism. It met the desires and passion of monks, nuns, and Buddhist followers in Vietnam, and created good conditions for Vietnamese Buddhists to develop their traditional attachment to the nation, promote the propagation of Buddhist doctrine, serve the homeland - the Socialist Republic of Vietnam - and contribute to bringing peace and happiness to the world. The report to the Congress emphasized the great importance of this event as follows: "After more than a hundred years of being enslaved by feudalism, colonialism, and imperialism, Vietnamese Buddhism can raise the flag of independence and freedom in the Social Republic of Vietnam as our community. This is a heyday of Vietnamese Buddhism, which could be found in the course of history, only under the Tran Dynasty with the Three Patriarchs of the Bamboo Forest Sect. Now, the heyday has returned and it is in your hands as representatives of the nine Buddhist associations, congregations, and denominations. From now on, there will be no differentiation between the Buddhists of the three regions. We now call ourselves by the most sacred and noblest term ''Vietnamese Buddhists.''

The Buddhist unification and the establishment of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation satisfied the expectations of the majority of monks, nuns, and Buddhist followers and were guaranteed by the policy to respect the freedom of belief and religion upheld by the Party and the State of Vietnam. Therefore, the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation has grown ceaselessly and consolidated its position in society. Up to now, the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation has had six congresses.

The First Congress took place at the Quan Su Pagoda (Hanoi) from November 4-7, 1981, with the participation of 165 delegates from nine denominations and congregations. This was the unification congress marked by the establishment of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation. Congress passed the charter and defined the line of activity under the motto "Dharma -Nation - Socialism." Venerable Superior Thich Duc Nhuan was nominated to be the Sangha-raja (Chief of the Buddhist Clergy) and Venerable Superior Thich Tri Thu President of the Executive Committee of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation.

The Second Congress was held in the Vietnam - Soviet Cultural Friendship Palace in Hanoi on October 28-29, 1987, with the participation of 200 delegates. Venerable Superior Thich Duc Nhuan was nominated to be the Sangha-raja and Venerable Superior Thich Tri Tinh Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation. The Sangha Council had 37 members and the Executive Committee had 60 members. The Congress approved the ordination of 60 venerable superiors, 22 superior monks, 12 superior nuns, and 28 nuns.

The Third Congress was also held in the Vietnam - Soviet Cultural Friendship Palace in Hanoi on November 3-4, 1992, with the participation of 227 delegates. Venerable Superior Thich Duc Nhuan was nominated to be the Sangha-raja and Venerable Superior Thich Tri Tinh Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation. The Sangha Council had 33 members and the Executive Committee had 70 members. The Congress approved the ordination of 72 venerable superiors, 130 superior monks, 32 superior nuns, and 103 nuns.

The Fourth Congress was held in the Vietnam - Soviet Cultural Friendship Palace in Hanoi on November 22-23,1997, with the participation of 320 delegates. Venerable Superior Thich Tam Tinh was nominated to be the Sangha-jara and Venerable Superior Thich Tri Tinh Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation. The Sangha Council had 67 members and the Executive Committee had 94 members. The Congress approved the ordination of 72 venerable superiors, 130 superior monks, 32 superior nuns, and 103 nuns.

The Fifth Congress was held in the Vietnam - Soviet Cultural Friendship Palace in Hanoi on December 4-5, 2002, with the participation of 527 delegates. Venerable Superior Thich Duc Nhuan was nominated to be the Sangha-jara and Venerable Superior Thich Tri Tinh President of the Executive Committee of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation. The Sangha Council had 85 members, and the Executive Committee had 95 full members and 24 alternate members. The Congress approved the ordination of 137 venerable superiors, 419 superior monks, 75 superior nuns, and 315 nuns.

The Sixth Congress was held in the Vietnam - Soviet Cultural Friendship Palace in Hanoi on December 13-14, 2007, with the participation of 1,500 delegates including 895 official delegates and 26 international guests from Laos, France, Germany, the Us, Thailand, India, and Czech, among others. The Venerable Superior Thich Pho Tue was nominated to be the Sangha-jara and Venerable Superior Thich Tri Tinh Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation. The Sangha Council had 98 members, and the Executive Committee had 147 full members and 28 alternate members. The congress approved the ordination of 1,448 dignitaries, among whom there were 372 venerable superiors and superior nuns, and 1,076 superior monks and nuns. The Congress approved the Amended Charter (including 12 chapters and 52 articles) that asserted the line of action of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation under the motto "Dharma - Nation - Socialism."

After nearly thirty years of construction and development, the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation has made many great achievements in Buddhist activities as well as social activities. The Proceedings of the Conference in celebration of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation assess the outcomes of its activities as follows:

In terms of organizational activities, this task draws special attention from the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation in order to unite the different congregations, denominations, and sects, and strengthen the Congregation to carry out the approved action program. At each congress, the organization was consolidated and widened. At the First Congress, the leadership of the Congregation included 50 members of the Sangha Council, 50 members of the Executive Committee. There were 6 specialized sections of the congregation, 28 managing committees in provinces and cities. However, at the Sixth Congress (2007), the leadership included 98 members of the Sangha Council, 147 full members, and 25 alternate members of the Executive Committee. There are 13 specialization sections and 54 provincial or city managing committees.

For nearly twenty-five years, the Vietnamese Buddhism Congregation has officially ordained 1,316 monks and nuns, of whom 231 are venerable superiors, 123 superior nuns, 544 superior monks, and 416 nuns. Every year, provincial or city associations organize a retreat season, which attracts the participation of over 80 percent of monks and nuns. Monastic status certificates have been issued to the majority of monks and nuns by the Congregation. The Congregation has organized 205 precepts-transmitting assemblies; 23,433 monks and nuns have undergone the ritual of "precepts-transmission." The Congregation has also issued "precepts-transmission" certificates to 23,727 monks and nuns. They included 4,659 monks and nuns for bhiksus; 4,556 for bhiksunis; 3,094 for siksamananas; 6,128 novice-monks; and 5,185 novice-nuns. The Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation was formed on the basis of the unification of different Buddhist associations, denominations, and sects from all over the country. Therefore, during its operation, the Congregation always respects the particular feature, religious practice, distinct traditions of different monasteries and denominations, especially Khmer Theravada Buddhism, and mendicant Buddhism. Along with the consolidation of the organization, the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation has amended the Charter at the past congresses to make it suitable for social situations and the developments of the Congregation. On October 10, 2005, the Standing Council of the Executive Committee promulgated Circular Number 404/TT/HDTS to the whole Congregation to seek suggestions for the amendment of the Charter, which would be presented to the Fifth Congress in 2007.

The Vietnamese Buddhism Congregation is organized into different levels from central to provincial, and district and grassroots, among which central and provincial levels play key roles.

At the central level, there are the Sangha Council and the Executive Committee. The Sangha Council includes venerable superiors of different Buddhist associations and denominations and sects in Vietnam, who are at least seventy years old and fifty years of monkhood, and are nominated by the National Buddhist Congress. The number of members of this Council is not restricted. The Sangha Council elects the Standing Council including President, Vice-presidents, Discipline Supervisors, a General Secretary, and Vice-secretaries. The Standing Committee of the Sangha Council is responsible for:

- Authenticating plenums and congresses of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation;

- Instructing and supervising the congregation's activities in terms of dogmas and discipline;

- Approving the ordination of such religious ranks as venerable superiors, superior monks, superior nuns, and nuns of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation;

- Promulgating messages on Buddha's Birthday, New Year, and the situation of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation in special circumstances.

The Central Executive Committee has a maximum of 147 members including venerable superiors, superior monks, the most virtuous monks, monks, nuns, and laypeople who are recommended by the previous Standing Board of the Executive Committee and nominated by the congress. The tenure of the Executive Committee is five years. The Central Executive Committee is the highest managing body of the Congregation and its activities between the two congresses. It defines the yearly action plan of the Congregation, which follows the resolutions of congress, and supervises the implementation of such a plan.

The Central Executive Committee of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation appoints the Standing Board including a chairman, three standing vice chairmen, other vice chairmen, a general secretary, two vice general secretaries, heads of specialization sections, members, a treasurer and inspectors. The maximum number of members in the Executive Committee is forty-five. The Chairman of the Executive Committee represents the Congregation in the legal aspects, in its domestic and international relations.

There are different sections in the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation:

1. Section for Clerical Affairs;

2. Section for Education for the Clergy;

3. Section of instruction for Buddhists including two subsections: for the Buddhist laity and for the Buddhist families;

4. Section of Propagation of Faith;

5. Section of Rites;

6. Section of Culture;

7. Section of Economy-finance;

8. Section of Social Charity;

9. Section of Buddhist International Relations;

10. Institute of Vietnamese Buddhist Studies;

11. Four supervisors;

12. Two legislation commissioners; and

13. Offices (Office 1 is at the Quan Su Pagoda at number 73 Quan Su Street, Hoan Kiem District, Hanoi; Office 2 is at the Quang Duc Ch'an Monastery at number 294 Nam Ky Khoi Nghia, District 3, Ho Chi Minh City).

Each provincial (municipal) executive committee has a maximum of forty-seven members and a standing board. Where conditions are not adequate, a representative committee can be established. The head of such a representative committee must be a monk or a nun appointed by the Central Congregation. The tenure of the provincial (municipal) committee is five years.

Districts, towns, and provincial cities can establish representative committees with a maximum of fifteen members for each. Communes and wards with many pagodas, convents, monasteries, prayer houses, monks, and nuns can have a representative appointed by the provincial executive committee on the recommendation of the district representative committee. The grassroots unit of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation is pagodas, monasteries, convents, houses of chastity and prayer.

In terms of training a new generation of talented monks and nuns in Buddhist doctrine and culture to undertake Buddhist missions at central, local, and international levels, the training program of the Buddhist Congregation at academics, colleges, intermediate schools, and primary schools is as follows:

First, the training institutes were known as Buddhist high schools. But now, they called Vietnamese Buddhist academies. Currently, there are four academies.

The Vietnamese Buddhist Academy in Hanoi with five (raining courses as follows: the first course lasted from 1981 to 1985 with 43 graduates; the second course, from 1994 to 1997 with 78 graduates; the third course, from 1998 to 2001 with 154 graduates; the fourth course, from 2001 to 2005 with 194 graduates; the current fifth course started in 2006 and will last to 2010, with 281 students.

Along with the above-mentioned courses, the managing committee of the Vietnamese Buddhist Academy in Hanoi coordinated with the University of Social Sciences and Humanities to open classes on Oriental Philosophy for graduates of the first and second courses at the Quan Su Pagoda. Up to now, 62 monks and nuns have registered for the classes; 27 have graduated.

The Vietnamese Buddhist Academy in Ho Chi Minh City has had six training courses: the first course was from 1983 to 1987 with 59 graduates; the second course from 1988 to 1992 with 101 graduates; the third course from 1993 to 1997 with 243 graduates; the fourth course from 1998 to 2001 with 285 graduates; the fifth course from 2001 to 2005 with 366 graduates. The current sixth course started in 2005 and will last to 2009, with 665 students.

The Vietnamese Buddhist Academy in Hue has had three training courses: the first course was from 1997 to 2001 with 164 graduates; the second course from 2001 to 2005 with 161 graduates. The current third course started in 2005 and will last to 2009 with 200 students.

The Khmer Theravada Buddhism Academy in Can Tho has opened only one course so far: from 2007 to 2012 with 68 students.

Currently, there are eight Buddhist Junior Classes with a total of 1,746 students; 1,382 students have graduated.

There are 31 Buddhist Intermediate Schools with 3,575 students; 5,357 students have graduated.

There are hundreds of Buddhist primary classes with thousands of students.

Concerning the education for the Khmer Theravada Buddhism, under the guideline of the Congregation and support of the administration at all echelons, Pali-language classes on Buddhism at primary, intermediate, and higher levels are now organized in Soc Trang, Tra Vinh, and Kien Giang with 2,500 students. The classes run efficiently and contribute to the success of the training programs for monks and nuns. Besides learning the Pali and Khmer languages, the students also attend complimentary education classes in Vietnamese in provinces. Moreover, the students also study at teacher training colleges and information technology classes as well.

With the assistance of the Government and local authorities, the congregation has sent 276 monks and nuns to India, Sri Lanka, China, France, Thailand, Myanmar, the US, Australia, and Taiwan, among others. Forty graduates from doctorate programs in Buddhism have come back home and are now working in central offices of the Congregation, research institutes, and provincial (municipal) Buddhism congregations. More than 300 monks and nuns are now attending Pho and Ma courses in those countries, 250 of whom are studying in India.

In addition to the above-mentioned training programs, in order to assist with the propagation of the faith, the congregation has held lectures on Buddhism in big lecture halls in Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, and other provinces and cities in the country. The congregation also opens classes for training monks to be lecturers; each class lasts for three years. Up to now, five classes have been organized with nearly a thousand graduate lecturers.

Canons are the main means for teaching Buddhist dogmas and instructing monks, nuns, and Buddhists to study and practice their religion. For the past time, most of the Buddhist canons, specifically the canons of Vietnamese Buddhism, have been published and widely distributed. Since the establishment of the Religion Publishing House in 1999, the Congregation has printed nearly 1,000 titles with about 6,000,000 copies. There are many sutras, including Dai bao tich (Ratnakuta), Hoa nghiem (Avatamsaka), Lang nghiem (Suramgama), Dai bat nha (Maha- prajana), Dai Niet ban (Mahanirvana), Phap hoa (Lotus Sutra), Phap cu (Dharmapada), Vien giac (Perfect Enlightenment), Hien ngu (Wise and Silly), Nhan qua thien ac (Cause-efect, Good- evil), Vu lan (Ullambana) and Tam bao (Ratnatraya); monastic rules (Vinaya), including Luat tu phan nhu thich, Luat tu phan ty kheo ni huyen ty, Luat ty kheo, Luat Bo tat, Luat hoc cuong yeu, Yet ma Chi yeu, Yet ma Chi nam, Gioi dan tang and Luat hoc co ban; treaties including Luan thanh Duy Thuc, Luan Duy thuc dai cuong, Luan Cau xa, Luan Bat nha Cuong yeu, Luan Trung quan, Phat hoc Pho thong, Ban do tu Phat, Phat hoc Khat luan, Phat hoc Nhap mon, Nghien cuu Lang gia, Nhan sinh quan Phat giao, Luan tang Nam tong, Tam quy Ngu gioi and Phat phap voi Thien tong. Also, history books concerning Buddhism have been published, including Lich su Phat giao Vietnam (History of Vietnamese Buddhism), Lich su Phat giao An Do (History of Indian Buddhism), Lich su Phat giao Trung Quoc (History of Chinese Buddhism), Lich su Phat giao The gioi (History of World Buddhism), Thieh su Vietnam (Vietnamese Ch'an Buddhism), Thien su Trung Hoa (Chinese Ch'an Buddhism), and Lich su Phat va Thanh chung (History of Buddha and Saints). In 2004- 2005, the congregation printed 16 books of canons for Khmer Theravada Buddhism, and has planned for another 13 books in 2007 and 2008. The congregation publishes three magazines: Tap chi Nghien cuu Phat hoc (Journal of Buddhist Studies), Tap chi Van hoa Phat giao (Journal of Buddhist Culture) and Tap chi Khuong Viet (Khuong Viet Journal) as well as a prestigious weekly called Tuan bao Giac ngo (Enlightenment Weekly) with ten thousand copies for each issue.

In terms of charitable activities, Vietnam got out of two protracted, severe wars not long ago, which left many social issues behind as well as new issues emerging as a consequence of the market economy, natural disasters, and epidemics. In the spirit of Buddhist compassion and the tradition of mutual assistance of Vietnamese people, monks, nuns, and Buddhist followers in Vietnam, under the leadership of the Congregation, have enthusiastically participated in social charity activities which are regarded as a focus of the Congregation. Currently, there are 25 Tue Tinh clinics, 655 consulting rooms, 165 charity classes, 16 day-care centers, and charity houses for orphans and handicapped children with nearly 7,000 children. For the past thirty years, social charity activities of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation have drawn over VND300 billion; thousands of tons of rice, clothes, and medicines; and thousands of canoes and boats in assistance for those who need it.

Since its establishment, the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation has carried out many international activities to develop relationships with Buddhists in other countries around the world. This effort has been promoted since Vietnam came into the period of renovation and integration. The Congregation has taken part in main international activities as follows:

In 1982: attending the Asian Buddhist Conference for Peace (ABCP) in Mongolia and the Conference of Anti-nuclear War Religious Leaders in the former Soviet Union;

In 1983: attending the Conference for Peace and Life, against Nuclear War in the Czech Republic and Slovakia;

In 1984: attending the Conference on Buddhism and National Culture in India and the Round-table Conference on the Universe without Nuclear Weapons in the former Soviet Union;

In 1985: attending the Conference on New Threats to the Holy Life and Our Responsibilities in the former Soviet Union;

In 1986: attending the Conference on Poverty, Arms Race and New Moral Order in the former Soviet Union;

In 1987: attending the Conference on Principles for Shared Security in the former Soviet Union;

In 1988: attending the Conference on Peace and Security in the Pacific Region in the former Soviet Union, the Praying- for-Peace Conference in Italy, and the Asian Protestantism Conference in India;

In 1989: attending the Asian Buddhist Conference for Peace in Laos;

In 1990: attending the World Religion Conference in Italy;

In 1991: attending the Buddhism and Peace Conference in Korea;

In 1992: cooperating with Japanese Buddhists to set up the Action Committee of Japanese-Vietnamese Buddhists;

In 1993: organizing the Fifth Disarmament Conference of Asian Buddhists for Peace in Vietnam;

In 1994: attending the Quang Son Buddha Conference in Canada;

In 1995: attending the Joint Self-cultivation Buddhist Conference in Taiwan;

In 1996: attending the Quang Son Buddha Conference in Taiwan;

In 1997: attending the Buddhism and World Peace Conference in Sri Lanka and the Conference on Looking for an Environment Morality in Cambodia, visiting and working with Mahachulalongcong University in Thailand.

In 1998: attending the Buddhism Propagation Conference in Japan, the Conference on Buddhist Culture Integrated with National Cultures in Germany and the Conference on the Explanation of the Eternal Message of the Buddha in Sri Lanka.

In 1999: paying a friendly visit to the Chinese Buddhist Congregation and establishing a relationship between the two sides;

In 2000: attending the World Religious Leaders Conference organized by the United Nations in New York and the Buddhism Propagation Summit Conference in Thailand;

In 2001: attending the Asian Religious Leaders Conference in Indonesia and the Workshop on the Training of Monks and Nuns in the Twenty-first Century in China;

In 2002: visiting and working with the American United Methodist Congregation, visiting the Japanese Buddhist Congregation; and attending the Asian Religions Conference in Indonesia and the World Buddhism Summit in Cambodia;

In 2003: attending the Asian Buddhism Conference for Peace in Laos and the Asia-Pacific Inter-religious Consultative Conference in Indonesia;

In 2004: attending the Graduation Ceremony from the M.A. course at Hanazabu Buddhism University (Japan), the World Buddhism Conference in Taiwan, and the Asian Buddhism Conference for Peace in Mongolia and Russia;

In 2005: attending the Prayer for Peace in Osaka (Japan) and the 2550th Vesak Anniversary in Thailand, visiting the Cambodian Buddhist Congregation and Lao Buddhist Congregation, and attending the World Buddhist Summit in Thailand;

In 2006: attending the Buddhist Festival in Zhejiang in China, the 2550th Vesak Anniversary in Thailand, and the Sakyadhita Congregation Meeting in Malaysia;

In 2007: attending the United Nations Celebration of Vesak Anniversary 2008 in Thailand, the Third Dialogue of Asian- European Faiths in China, the Asian-Pacific Inter-religious Dialogue in New Zealand, and the Inter-regional Youth Forum in Australia.

These international activities of the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation are considered great Buddhist activities, which not only create conditions for Vietnamese Buddhism to be integrated internationally but also popularize Vietnamese culture to the world.

The Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation does not have accurate statistics on the number of monks, nuns, Buddhist followers, or places of worship in different time periods. Only information from during the period before the Renovation and current statistics are available. According to the Congregation's statistics, in the mid-1980s, there were about 7 million Buddhist followers; 15,000 monks and nuns; and 8,500 places of worship. Currently, there are nearly 10 million Buddhists who follow the Triratna (among 40 percent of Buddhists and 70 percent of the Vietnamese people influenced by Buddhism in terms of lifestyle and culture). There are nearly 40,000 monks and nuns (Mahayana: 28,000; Theravada: 9,000; Mendicant Buddhism: 1,000), over 15,000 pagodas (Mahayana: 14,605; Theravada: 693), 3 Buddhist Academies (in Hanoi, Hue, and Ho Chi Minh City), 7 Buddhist higher classes and 31 Buddhist intermediate schools. The action scope covers 64 provinces and cities across Vietnam, 52 out of which have managing committees and 3 have representative committees.

Given these achievements, many Buddhist researchers in Vietnam and in the world have noted that for nearly thirty years of national unification, Buddhism in Vietnam has made incredible advances, creating the apex of the movement for Buddhism amelioration in Vietnam.

In summary, Buddhism came to Vietnam in the early days of national history. The introduction of Buddhism into Vietnam was quite early in comparison with other countries in this region. It entered Vietnam peacefully, either directly from China and India, or via Cambodia and Champa.

Vietnamese Buddhism is the convergence of both Mahayana (from the North) and Theravada (from the South) sects and has experienced influence from the three big sects of Mahayana Buddhism: Ch'an Pure Land sect, Tantrism, and Ch'an Buddhism with the last being the most profound. At the same time, Vietnamese Buddhism has also been under the influence of Confucianism and Taoism as well as the national traditions, customs, and folk beliefs, which make up its peculiarities. Of note is the concept of "three doctrines from the same source."

In its history of nearly twenty centuries with its apex lasting from the tenth to the fifteenth centuries, Vietnamese Buddhism has built a patriotic tradition with a strong attachment to the nation, national protection, and security for people. At the same time, it has contributed to the development of the national culture, mind-set, morality, and lifestyle.

Currently, monks, nuns, and Buddhist followers from all over Vietnam are rallied in the Vietnamese Buddhist Congregation operating under the motto: "Dharma - Nation - Socialism." It is making important contributions to the renewal process of the nation, building for itself great prestige and exerting impact on Buddhism in this region and the world alike.