Vietnamese names can be veritable Chinese puzzles for the unwary foreigner. Shortening a Western name is simple enough. The French M. Louis Simon becomes: "Monsieur Simon", the British Mrs. Elizabeth Hodgkin, "Mrs. Hodgkin". There is no chance for a mistake; you simply use the family name, which usually comes last.

The Rules of Vietnamese Names

But what is the rule for Vietnamese names like Le Lam, Tran Van Ba, Nguyen Thi Bang Tam? The order of the names is reversed: the family name precedes the given name. But in names with more than two syllables, the family name may include either the first or the first two syllables, and the given name, the last or last two syllables.

To complicate matters more, a Vietnamese is usually called by his given name, and only very exceptionally by his family name. At an international conference, the Japanese chairman, wishing to call on a Vietnamese member named Nguyen Huu Phu, called out his family name: "Mr. Nguyen". Alas, Mr. Nguyen Huu Phu, who is normally addressed as Mr. Phu, paid no attention to this call, believing it to be meant for someone else in the audience.

A Vietnamese name is made up of the name of the family clan (tinh or ho) and the given name. These two elements may or may not be linked by a middle element, often Thi for a woman and Van for a man. Thus, in Tran Van Ba, Tran is the family name, Ba the given name, and Van the middle element. In Nguyen Thi Bang Tam, Nguyen is the family name, Bang Tam the given name, and Thi the middle element. In Nguyen Khoa Dieu Hong, Nguyen Khoa is the family name, Dieu Hong the given name.

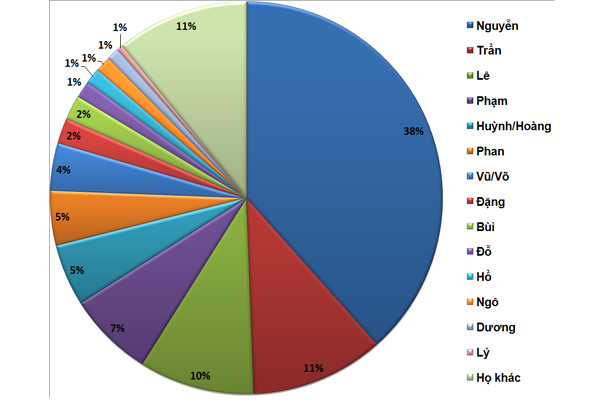

It is estimated that the total number of clan names is not more than 300, the most frequently met being Nguyen. It is the father or grandfather who usually chooses the given name, taking his inspiration from the names of plants, flowers, fruits, or animals, or such abstract notions as the Vietnamese zodiac signs of the zodiac or moral virtues.

It is forbidden to give the name of the parents, an ancestor, a member of the royal family, 'or a god worshipped by the community. Even speaking such names was taboo. In the old days, any candidate in an official examination who unwittingly used one of the royal names in his writings was failed and severely punished.

The Diversity of Vietnamese Names

In former times, between birth and death, a Vietnamese might have a dozen names. There was no registry office, and a newborn child was not immediately given a formal name. It was first called by a nickname, intentionally designating an ugly or obscene object, so as to ward off evil spirits: thang cu (penis), cai him (vulva), thang do (the red one).

At the age of two or three, he was given a private name (ten tuc), which would be used at rites following his eventual death (ten cung com: name to invoke the dead to return to accept the offering of rice).

Depending on circumstances (examinations, marriage), the individual adult - often the male in particular - was given an official name (ten bo: name recorded in the village registry). In some cases, it was the same as the private name.

People of some distinction would give themselves a pseudonym (ten hieu), usually made up of two classical Chinese ideograms evoking a geographical location or a moral quality. For instance, Tan Da, Mount Tan and River Da, both located at the place of birth of the poet with that pseudonym; or Bach Van Cu Si, the Hermit at the Cottage of the White Clouds. A literary name (ten chu, ten tu) was a kind of laudatory comment made up of classical Chinese ideograms explaining the content of the official name.

After his death, a man was given a posthumous name (ten thuy); his private name also became a posthumous name and was taboo for his descendants (ten huy, ten hem).

In conclusion, let us note that the religious names of Buddhist monks begin with the word Thich (phonetic transcription of Sakya), But the short names of Buddhist nuns with the word Dam or Dieu.