After first visiting the south of Vietnam, and before traveling to the north of the country, a foreign friend once asked me if I thought that differences in regional interests and differences in northern and southern mentalities, deepened by twenty years of war and separation, could affect our national identity?

The Mental Differences between Northern and Southern Vietnamese in the 17th & 18th Century

Are there mental differences between Northern and Southern Vietnamese? In answering such a question, it would first be useful to define the exact notions of north and south Vietnam. The country was first cut in two by the Nguyen and Trinh seigneurs, who, under the pretext of serving the Le dynasty, waged a war that was to last nearly a century and a half in the years 1627 to 1772. The demarcation line was the Gianh river in Quang Binh province, north of Hue. Foreigners called them northern part Tong king (Tonkin) and the southern part Cochinchina.

The Mental Differences between Northern and Southern Vietnamese Under French Domination

The country, reunified in the late 18th century, was conquered by the French in the second half of the 19th century. Under the colonial regime, which lasted between 1884 and 1945, the country was divided into three parts: the North which was referred to as Tonkin, the Centre, called Annam, and the South referred to as Cochinchina. Tonkin and Annam were proclaimed by the French as protectorates, while the South was administered as a colony. The Independent People’s Republic, proclaimed by Ho Chi Minh and restored unity in 1945.

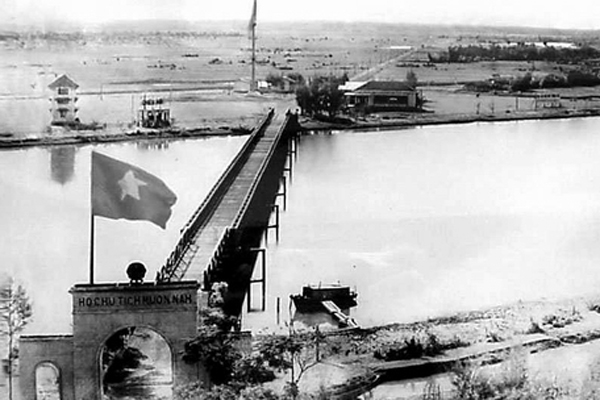

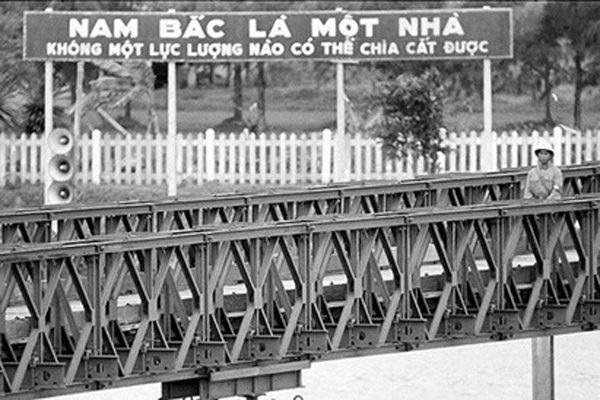

The Geneva Conference, held in 1954, and which pull an end to the First Indochina War fought against the French, divided Vietnam at the I7th parallel for twenty years during the Second Indochina War against the Americans. Thus the border between the North and the South has changed three times throughout history.

The Mental Differences between Northern and Southern Vietnamese Today

At present, when speaking of “the people of the south”, we think of the inhabitants of the Mekong delta. Though their mentality is different from that of the rest of the country, it is by no means secessionist. The French colonialists failed to realize this when they attempted to create the autonomous republic of Cochinchina in 1946. The Americans made the same mistake when trying to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail which connected the north and the south, As the French historian Philippe Devillers noted at the start of the First Indochina War, “Cochinchina, Nam Bo, is an integral part of Vietnam, whose ethnic, geographical, historical, cultural and psychological unity is a fact one cannot deny, a fact recognized indeed by French historians and geographers.”

One cannot deny the different mentalities of northern and southern people. In Europe, Nordics are generally less easy to approach and less talkative than Mediterraneans, perhaps because the Nordic countries are in a colder climate. In a way, the same applies to Vietnam But in Vietnam climate plays a less important role, because while only the north has a true winter, both north and south are part of the same tropical monsoon region, hot and humid. Rather, explanations should be sought by carefully considering history. The Vietnamese population has always been made up of wet rice farmers working on submerged fields. They created an original cultural identity in the basin of the Red River in the first millennium B.C. After freeing themselves from a thousand years of Chinese domination they began advancing southward, reaching the Mekong delta in the 17th century.

The first Viet settlers-famished peasants, peasant-soldiers, adventurers, and banished criminals – cleared generous virgin land. They did not have the hard work and chronic want that was the lot of northern farmers, plagued by the scarcity of land and the frequency of natural calamities such as floods. The villages they built were not, as in the north, isolated communities surrounded by bamboo hedges and burdened by age-old customs, rites, and taboos marked by Confucian rigor. New religions, such as Cao Dai and Hoa Hao, unknown in the north, attracted millions of followers. No distinction was made between “guest” and “host” villagers. The Viet lived in harmony with other ethnic groups in the region such as the Cham, Khmer, Ma, Stieng, and Chinese. There were enough resources for all. The Chinese, many of them political refugees, did a thriving trade. The regime of direct colonial rule under the French and the capitalist economy under American sway no doubt reinforced the psychology of the “people of the South”, some traits of which called to mind the American spirit of the “Frontier.”